-

The birth of GRIPS from the spirit of cabaret

By Volker Ludwig

GRIPS Theater is a child of the student movement and cabaret. That is the secret of its success. The 50s and 60s were the time of the Cold War. Anti-communism held the West together, we lived in a deeply anti-enlightenment world. An ideal time for satire. In West Berlin, the thorn in the flesh of East German communism, political-literary cabaret flourished: Islanders, porcupines, voles and ironing boards impaled grievances, but without even noticing their cause, the social conditions.

In 1965 a majority of the ensemble and its Managing director left the “non-political” voles and made me, as the “most political” Berlin copywriter, head of a new left-wing troupe. We called ourselves Reichskabarett Berlin and found space in Wilmersdorfer Ludwigkirchstrasse (today the “Hamlet”): a narrow place, the living room-sized stage in the back, the living-room counter in front, soon a popular meeting place for the extra-parliamentary opposition.

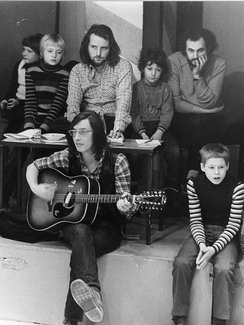

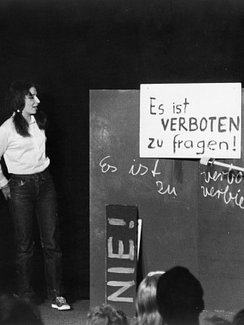

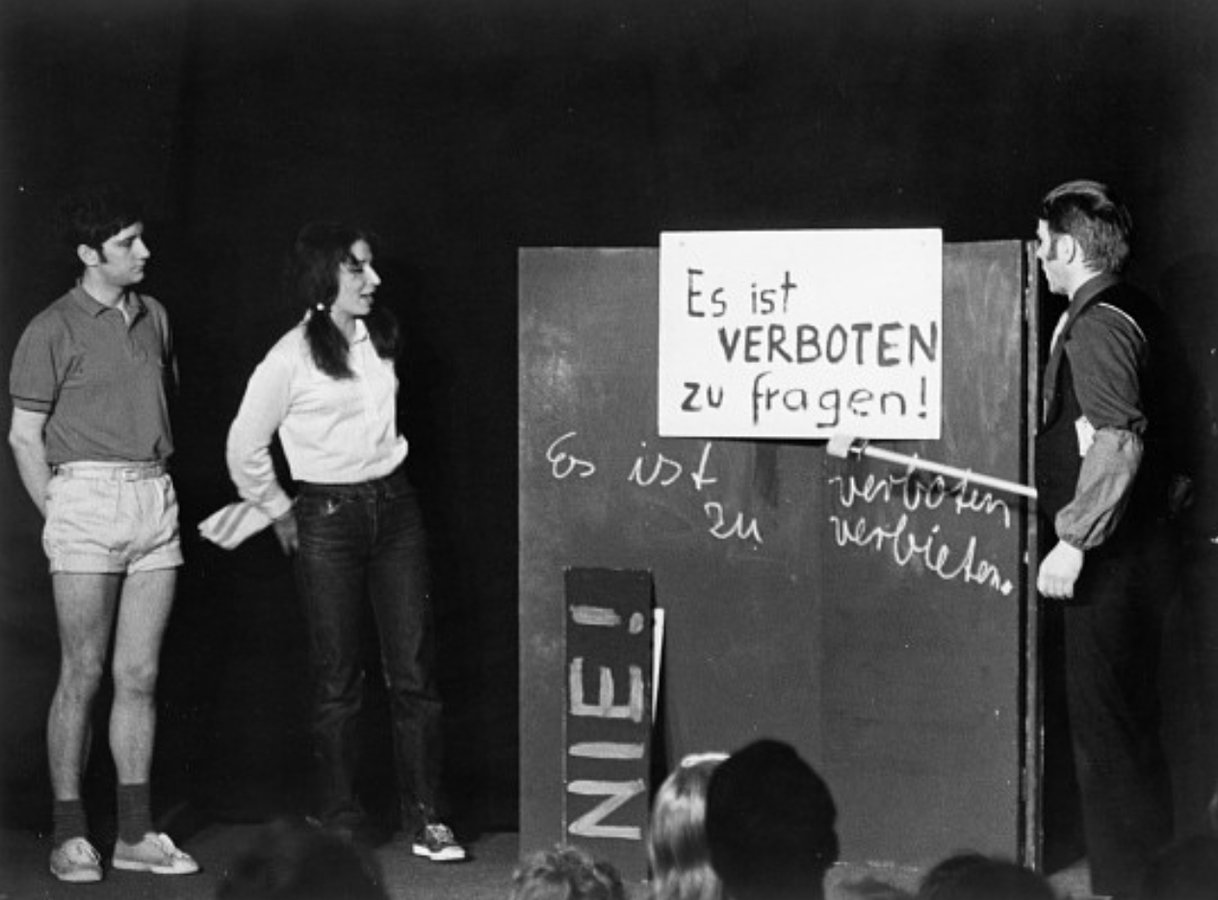

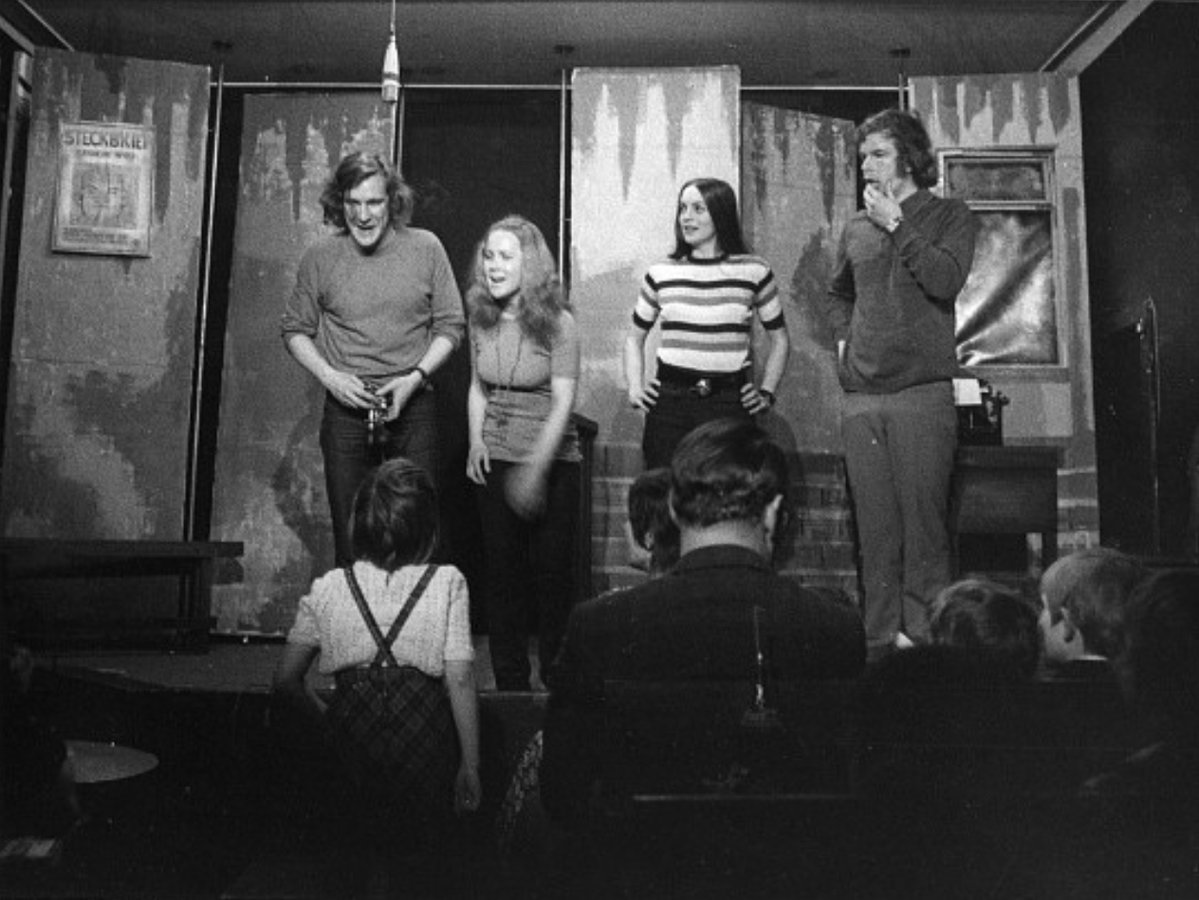

Stokkerlok und Millipilli 1969

Stokkerlok und Millipilli 1969

Stokkerlok und Millipilli 1969, in the picture: Theodor Puechel, Barbara Maasch, Dieter Kursawe With our second programme “Bombenstimmung”, a factual Vietnam War review by the 22-year-old Frank-Patrick Steckel (with contributions from the equally young SDS member Detlef Michel and several old masters), the Reichskabarett established itself in 1966 as the satirical voice of the student movement, especially the SDS wing around Rudi Dutschke. Serious cultural criticism suddenly wished we were outraged behind the wall, we lost stunned friends and all jobs at RIAS, but we had the truth on our side and felt great. On Friday nights they sang, those who dared got ten marks, and that was a lot: Hannes Wader, Ulrich Roski, Reinhard Mey and Katja Ebstein (then still Witkiewicz), Insterburg and Co. met here and became cult like Ortrud Beginnen. Peter Rühmkorf read and Hüsch and the Floh de Cologne made guest appearances.

And just so that the place would not be empty in the afternoon, our manager invented a “Theatre for children in the Reichskabarett” in June 1966, which was very unusual, because back then there were only Christmas fairy tales for children. The cabaret artists had nothing left for this children’s theatre around Sigrid Hackenberg and Horst Jüssen. Despite great success and the Brothers Grimm Prize in 1967 for “Kasper und der Löwe Poldi”, we were rather embarrassed about the company. We did not have the idea to use this genre politically and turn it upside down until three years later – in the spring of 1969, when we broke with the children’s theatre troupe. Instead of dealing with the content with us, it moved to the Theater Tribüne, where it soon came to an end.

In order to plug the budget hole, the star cabaret artists had to do something themselves. Set designer and caricaturist Rainer Hachfeld wrote “Stokkerlok and Millipilli” with me in three and a half weeks, Kursawe and Wiehe played the dismissed engine driver Stokkerlok and the locomotive owner Kratzwurst, Hobby: painting “Prohibited” signs The premiere was on 17 May 1969. The critics panned the play just as furiously as they had “Bombenstimmung” three years earlier.

A year later it received the Brothers Grimm Prize and Robert Wolfgang Schnell stated in his laudation: “Hachfeld and Ludwig show that they are not imaginative aesthetes, but rather have moral passion, without which nothing beneficial can be done in the field of theatre”. The play was re-enacted in over 100 theatres around the world. Why does the story of GRIPS begin with “Stokkerlok and Millipilli”?

Despite its fairytale packaging, it contained everything that defines GRIPS and was part of the Enlightenment concept in 1968: It is anti-authoritarian, emancipatory, socially critical, optimistic. It represents the interests of its audience, wit and solidarity are the weapons of the oppressed. It is cabaret, only for a new audience: punchy, cheeky, with catchy songs.

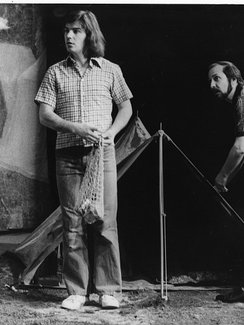

Balle, Malle, Hupe und Artur 1971

Balle, Malle, Hupe und Artur 1971

Balle, Malle, Hupe und Artur 1971, in the picture: Jörg Friedrich, Barbara Hampel, Dagmar Dorsten, Ulrich Gressieke For us, like adult cabaret, the children’s theatre was now “a means of influencing social conditions”, true to the Brecht motto: “Whoever has recognised his situation, how can he be stopped?” The collapse of the student movement also affected the Reichskabarett.

Only the children’s movement remained little affected by the ideological trench warfare. Whether one sought salvation in Moscow, Beijing or in the SPD was a minor matter when everyday life demanded new anti-authoritarian educational concepts: Our children were annoying across factions. Quite a few left-wing students became primary school teachers in Neukölln and Wedding.

In addition to the children’s places, their school classes shaped our audience, which was largely proletarian as a result. What we missed so painfully in cabaret, we finally found: An audience of all classes including the precarious. Our love for this audience made it easy for us to say goodbye to political cabaret. And the question of the meaning of our actions never arose again.

-

The 70s: GRIPS prevails

By Volker Ludwig

The rapid rise of GRIPS Theater was accompanied by resentment and ideological resistance. Right from the start, “education experts” complained that we were just giving the poor children their own bleak everyday life, inciting them and making them unhappy instead of taking them away to an ideal world. The truth was, however, the children were more enthusiastic to see themselves with their everyday worries at the centre of things than anything else, to be taken seriously, to discover what others like them are doing, that the world can be changed, and above all that there is a lot to laugh about. As an aid to judgment, we only invited school classes to our second premiere, “Maximilian Pfeiferling”, in November 1969, and put critics and experts at the very back. That was a great help. After the performances, children stormed us with suggestions as to what the next play should be about. Everything they suffered from: roaring and hitting parents, school classes that were too big, injustice, bans, stupid boys/girls, no place to play, etc. We made cheeky comedies out of them, mostly set in the proletarian milieu, with the aim of boosting children’s self-confidence and stimulating their social imagination; Encouraging theatre with the dialogue wit of cabaret and songs to sing along with (“Man muss sich nur wehren,” (Just defend yourself) “Trau dich” (Dare to), “Wir werden immer größer” (We are growing up), “Doof gebor´n ist keiner” (Nobody is born stupid), “Mädchen lasst euch nichts erzählen” (Girls, don’t let them tell you stories) and many others).

By the end of 1973, another seven plays had been created, from “Mugnog Kinder!” to “Ein Fest bei Papadakis". In the absence of alternatives, the West German City and State theatres rushed to them, from Bremen to Constance, Cologne to Ingolstadt; they opened their studios and painting rooms and performed GRIPS. Outside the Christmas season! All year round! Each of the nine anti-authoritarian plays were re-enacted in 30 to 50 theatres, soon also in Sweden, Switzerland and elsewhere. This is how the children’s theatre landscape that exists today was created. Thanks to the liberal WDR Cologne, all of these productions were lavishly recorded and broadcast on Saturdays in the first program. More GRIPS presence was hardly conceivable. Our sixth world premiere, Mannomann! in May 1972, took place in the Forum Theatre on Kurfürstendamm, an avant-garde stage that we moved into as a subtenant because of the separation from cabaret required by the Senate for subsidies. That gave us 100,000 marks a year, and we called ourselves “GRIPS Theatre for Children”. GRIPS owes the discovery of the space stage to the Forum Theatre. The apartment in “Mannomann!”, Doof's classroom remains stupid and the camping ground for the “Fest bei Papadakis” was in the middle of the room, with the audience all around, in close proximity to the actors. When we took over the former “Bellevue” cinema on Hansaplatz, which was already leased by Aldi, we made it a condition of converting it into an arena stage. The new house on Hansaplatz also offered the opportunity to establish a youth theatre with a rock band. Again and again, teachers from sixth grade school had complained that they could never go to the theatre again. There was nothing for older ones. So, together with co-author Detlef Michel, and later also with the actors, costume designers and prop masters, I researched for a year in Neukölln school playgrounds, in classrooms and recreational homes about hopeless secondary school leavers for a play that ultimately became realism In the sense of Brecht, it was hard to beat: “Das hältste ja im Kopf nicht aus” (1975) was sold out for three years. 50,000 secondary school students saw the cult play in which, according to the CDU, they were “incited to violence with foul language”. But the theatre clientele also poured in. At the same time, the Christian Democrats (fortunately forming the opposition) began a long-term smear campaign against GRIPS by banning the performance of “Mensch Mädchen!”, supported by parts of the Springer press. While we were initially amused by the claim that we were “the representatives of this whole Bolshevik cultural revolution,” we stopped laughing when the CDU parliamentary group in the House of Representatives unanimously demanded the abolition of all subsidies and a ban on school class visits for three years in a row. While “Das hältste ja im Kopf nicht aus” celebrated triumphs at the Berlin theatre meeting in 1976, GRIPS was banned in all CDU-ruled Berlin districts; visits to GRIPS by teachers were entered in their personnel files. The Berliner Morgenpost alone produced 29 inflammatory articles in seven months. Quote: “Subsidies to GRIPS mean we are bringing up a bunch of psychopaths, poor kids who one day will break apart. Before that, they will have broken other things too. “When CDU officials finally claimed that we were supporters of the Baader-Meinhof gang, I was forced to sue for revocation. And lost in 1977 in the last instance before the Berlin Supreme Court. But the generally expected end for GRIPS did not materialise. On the contrary: The indignation of the liberal press and the public about this absurd judgment and the wave of solidarity were so enormous that the smear campaign turned into an advertising campaign for GRIPS. We had never been so sold out.

-

“The history of GRIPS Theater is its plays”*

By Volker Ludwig

GRIPS was and is an author and premiere theatre. Due to necessity, it developed all 29 plays of the first 15 years itself (the first “foreign” play was “Medeas Kinder” from the Unga Klara Theatre Stockholm in 1984). In close cooperation with the actors, it was mainly a quartet of authors who did the writing, mostly in alternating teams of two: Volker Ludwig (18), director Reiner Lücker (10), stage designer and political cartoonist Rainer Hachfeld (6) and journalist Stefan Reisner (6), plus Detlef Michel as co-author of all youth plays (4). Ludwig wrote songs for 26 (to date 52) plays, set to music by Birger Heymann, who accompanied the performances from “Mugnog-Kinder!” on the guitar and encouraged the children to sing along. No play was created in the blink of an eye, on the contrary: Each was hard-won, a learning process, a new milestone, an original. There were no role models for a new children’s theatre. Bert Brecht was studied, our idols were Dario Fo, Ariane Mnouchkine, Peter Brook and our guest San Francisco Mime Troup with their slogan “Theatre is Comedy”. Since there was always agreement about the goals of GRIPS, fortunately the struggle for the next play was not about ideology, but rather about craft.

The actors played an enormous role with their wealth of experience from hundreds of performances in front of children. Individual actors were co-authors and for years their mentions were supplemented by “and ensemble” until it was no longer a matter of course, otherwise it would have belonged behind every director’s statement. The subjects of the plays come from the authors or the ensemble, but a play is not commissioned until a convincing story is available. A subject is not an idea for a play. On the subject of guest workers, for example, it took us two years to find the ideal plot, “Ein Fest bei Papadakis” (1973). Every scene presented, every dialogue has to be written as perfectly as possible from the start, everything else is a waste of time. Improvements by means of rehearsals and additional ideas from everyone involved give the play additional shine. After the premiere, the text is set in stone, unless experiences with the audience still call for changes, which is rare. How do adult actors portray six-year-old children without it being embarrassing? What is the function of songs? How does joint writing work? The rehearsals for our fourth play, “Balle Malle Hupe und Artur” (1971), lasted ten whole months. Three actors competed with me in writing the scenes. The drudgery was successful. The play is still an international hit today.

Almost all GRIPS plays tell realistic stories from everyday life in Berlin. Exceptions were the so-called Third world play “Bananas” (1976) and the first environmental play “Wasser im Eimer” (1977), both at the request of teachers who were friends and who were allowed to post-treat these materials that were not in the framework plan in this way, even had to, at the instigation of the CDU, in order to “detoxify” what they saw after a GRIPS visit. Other exceptions were the first adult play “Eine Linkist Geschichte” (1980), which ends in the present but begins with the student movement in 1966, and “Ab heute heißt du Sara” (1989) after Inge Deutschkrons “Ich trug den gelben Stern”, which premiered five days after the right-wing Republicans moved into the House of Representatives, making it the most up-to-date play in town. Another historical piece of Berlin followed in 2008 with “Rosa”. With the larger new house, the lack of suitable authors and the misery of non-existent plays threatened to become an existential problem. The plays came more and more unfinished to the test. So we looked for a dramaturge and found him in Wolfgang Kolneder, director of the Tübingen room theatre, whom the Forum Theater courted, but who preferred GRIPS, because it was “a theatre that is needed”. He was soon the intellectual mastermind, brought order to our collective working methods, stepped in as a director for “Das hältste ja im Kopf nicht aus” and was invited to the Berlin theatre meeting. For 14 years he was the defining director of the house, the huge successes of the youth plays, “Eine Linke Geschichte”, but above all of “Linie 1” would be unthinkable without him. But what would GRIPS be without its actors! Without the charismatic trio Ahrens / Lehmann / Veit, who were the backbone (and gurus) of the ensemble for over 40 years, without their beloved colleagues who started at GRIPS, they stayed and learned for five to six years and today our films, TV plays and, above all, crime scenes benefit from them! They are not only the inspirers of the plays, they are their directors! Almost 100 of all 180 GRIPS productions were staged by experienced GRIPS actors, first and foremost Dietrich Lehmann and Rüdiger Wandel (almost 20 each), as well as Thomas Ahrens and Hermann Vinck (8 each), who each wrote five plays, and since 2011 Robert Neumann (until now 6). External directors had a hard time with GRIPS. It is all the more astonishing that in the past 20 years three “outsiders” have convinced the ensemble from the beginning, even fascinated them, that they quickly became part of the house: the beloved Franziska Steiof, with whom I wrote “Baden gehn” and “Rosa” and whose shocking death in 2014 left a ghastly wound, as well as Yüksel Yolcu and above all Frank Panhans, Faust Prize winner with “Cengiz und Locke”. With the authors, on the other hand, things looked bleak. The old people stopped or only wrote one more time (Lücker 1990, “Auf der Mauer auf der Lauer” Hachfeld 1996,“Eins auf die Fresse”, still on the program today).

The temporary salvation came in 1986 with “Linie 1”, which brought all the qualities of GRIPS theatre to a head in a musical review in such a way that it became the greatest success that a German play has ever had. The performance was so expensive that at the end of the year we were faced with bankruptcy again, from which our former enemy, the CDU, freed us this time. From now on, all evening plays were compared with “Linie 1”, which did not make life any easier. A veritable new GRIPS author did not appear until 1996: Lutz Hübner wrote his first youth play “Das Herz einer Boxer” (with Axel Prahl and Christian Veit) for us, soon the most performed play after “Linie 1” on German stages. The in-house productions “Alles Gute” (1998) and “Hallo Nazi” (2001) followed, and since then we have been performing his new plays with pleasure, from "Nelly Goodbye” (2004) to “Frau Müller muss weg” (2012). But we are still looking for authors as ever. Especially “for people aged 5 and over”. There is light at the end of the tunnel. Thanks to the “Berlin Children’s Theatre Award” author competition by GRIPS and GASAG, we discovered two authors who are both already working on their fourth play for GRIPS: Milena Baisch and Kirsten Fuchs. The future seems saved. I can now take a step back.

*The title of this chapter is a quote from Wolfgang Kolneder

-

GRIPS around the world

By Volker Ludwig

In 1975, Klaus Vetter, theatre advisor at the Goethe Institute, came up with the idea of presenting the Berlin GRIPS as a German specific outside of Europe. Applications had already been received from three Brazilian institutes, so I travelled to Brazil in 1976, still at the time of the military dictatorship, in order to get to know the children’s theatre scene and its makers in five one-week seminars, while Wolfgang Kolneder staged “Stokkerlok und Millipilli” in Curitiba (other plays had no chance with the censorship). A theatre with a social function, for young and old, in the guise of comedy, was something completely new for the Brazilians: An explosive subversive vehicle to bring the real problems of the audience to light effectively. “Pedagogy of the oppressed” by Paolo Freire was quoted again and again, there was heated discussion every night in manageable rounds, while in public they preferred to let me talk alone for fear of informers. The long-term effects of our trip were overwhelming: From the Curitiba troupe alone, four new groups emerged that adapted GRIPS pieces, “Max und Milli” toured Rio for five years, São Paulo brought “Alles Plastik” and several troupes developed GRIPS pieces for and with favela residents. The name GRIPS became synonymous with non-escapist theatre in general. Klaus Vetter wrote about this in 1994: “Back then, the stone was thrown into the water. The water made waves. Today, plays from GRIPS Theater are translated, adapted and staged in all parts of the world and in a wide variety of cultures, and materials and plays are produced and tried out using the GRIPS method in the form of guest directors, production workshops and writers’ meetings at the request of many theatre makers from Vancouver to Manila to Wellington, Volker and his directors travel for or through “Goethe” into the inner and outer landscapes of the theatre universe in order always to come back to where they started in Brazil: Listening, watching, thinking, stimulating and shaping together. Encounter others and different things. You could also call it a “cultural exchange” if this term had not been misused so often.”

In 1979 GRIPS started its “1st International Children's and Youth Theatre Meeting”, financed by the Berliner Festspiele with 200,000 DM. Subtitle: “Ten years of emancipatory theatre”. For the first time we were able to introduce our foreign friends to people from Berlin, the National Theatre in Gothenburg, Teatro del Sole Milan, Proloog from Eindhoven, three Danish and three French-speaking troupes and two times “Maximilian Pfeiferling” from Zagreb and Athens. A year later, England was also hit by the GRIPS wave, starting with “Things that go bump in the night” (“Max and Milli”) at the Unicorn in London. Translator Roy Kift wrote “Stronger than Superman” for GRIPS in the same year. The highlight of all tours so far began in Amsterdam in June 1980 with the guest performance of “Eine linke Geschichte” (premiered in May): The three-week participation in the “Holland Festival” with seven productions and 24 appearances in six cities. There were 20 minutes of standing ovations in Utrecht for “Die schönste Zeit im Leben”. The crowning of the second Theatre meeting: In 1981 the Werkheater Amsterdam offered “Abendrot und Waldeslust” and a Turkish “Mannomann! from Ankara”, which then staged 40 performances in Berlin schools. The international reputation of our children’s and youth theatre meeting was as enormous as its funding was pathetic. For the 1983 edition, I organised a joint tour for troupes from overseas with the Holland Festival and NIFTIE London. But then the reaction struck: The new Kohl government, which financed the Berliner Festspiele, cancelled the ridiculous 200,000 DM completely and without justification four months before the festival began. The tour of Green Thumb Vancouver, which co-produced “Trummi kaputt” with GRIPS, fell through, as did that of the furious New York Creative Arts team, which then broke down, a later act of revenge by the CDU. The exchange broke off and from then on we had to rely on festivals for guest performances. “Die schönste Zeit im Leben” and “Alles Plastik” still celebrated triumphs in Nanterre and London, otherwise the focus was again on the Goethe Institute with workshops, seminars and guest directing. Reiner Lücker staged in Lima, Jörg Friedrich in Kenya and Indonesia, Thomas Ahrens in Atlanta and Wolfgang Kolneder, the language genius, in Canada, Hong Kong, Japan, Ireland, Norway and occasionally India. There, in Pune, in 1983 I met Mohan Agashe, psychiatrist and nationally famous actor, who saw GRIPS as just the theatre that India needed. His “GRIPS Project” started in 1986 with Wolfgang Kolneder’s production of “Max und Milli” in Marathi. After years of workshops, “Mannomann!” followed, directed by Shrirang Godbole, Wolfgang’s assistant, now a major film producer, playwright and still involved in the GRIPS movement, which quickly spread across the Indian continent. At the anniversary festival “Coming to Grips with India” in 1996 in the Prithvi Theatre Mumbai, I saw “Max und Milli” alone in three Indian languages. The countless adaptations of GRIPS plays gave way more and more to Indian plays that followed the “GRIPS method”, which was entirely in our favour. The GRIPS country India has cut itself off, has blossomed and flourished, we have made ourselves superfluous. Mohan Agashe calls the organisation of his GRIPS movement “D.A.T.E .: Developing Awareness Through Entertainment”. What better way to define GRIPS?

In 1984 I promised the GRIPS musicians (as compensation for a youth play without live music) a veritable musical, which I also booked for the 1986 Dublin Theatre Festival; there had to be so much pressure. “Linie 1” premiered in April 1986, five months later we performed in the English language that GRIPS director Rod Lewis had practiced with the actors in Dublin and London, with sensational success that continued everywhere: 1987 in Vienna, Turin, Paris and Amsterdam, 1988 in New York, Brisbane, Melbourne, Jerusalem and, equally exciting, in Karl-Marx-Stadt, Dresden and Halle. Prague and Moscow followed later (together with “Ab heute heißt du Sara”), finally Pune and Mumbai in 2001, where enthusiasm knew no bounds thanks to Pete Gilbert’s ingenious translation and sub-titling, and in 2003 the return visit to the Hakchôn Theatre in Seoul. Money was also running out at the Goethe Institutes. Even so, Thomas Ahrens toured the USA and South Asia with “Sturm und Wurm”, and Axel Prahl and Uli von Lenski toured with “Vorsicht Grenze” for years through the Baltic States, Poland, the Czech Republic, Turkey and Russia, where we were the first western theatres allowed the performances in Perm, Yekaterinburg and Omsk. Thanks to “Linie 1”, the worldwide re-productions boomed again. Without us being aware of it, we had apparently met a lot of typical metropolitan residents with our Berlin people, who are recognised all over the world, which was pointed out to us again and again. No wonder that in addition to countless re-productions, there were just as many new adaptations that transferred Berlin’s “Linie 1” to their respective cities. We were particularly fascinated and touched by the versions from poor Calcutta and the ingenious new poetry by the charismatic Korean singer and composer Kim Min'Gi, which surpasses everything in quality, depth and musicality and with over 4,000 performances so far “Linie 1” is the most successful German made play of all time. We were able to invite four adaptations to Berlin: In addition to Seoul, the wonderfully underground version from Vilnius and the exciting, cheeky, lively shared taxi versions from Namibia and Yemen. But also the children’s plays, our real profession, are staged around the world: Continuously from GRIPS Theater Karachi, from the Hakchôn Theatre Seoul, in Nagoya, Japan, all over India, Greece, Turkey, from Canada to Uzbekistan, Brazil to Georgia. GRIPS has become an integral part of world theatre.

-

The new millennium

By Philipp Harpain

At the beginning of the 2000s the cornerstones on the stage were the big musicals: “Café Mitte” tells of the upheavals in the heart of Berlin (premiere 1997), “Melodys Ring” (2000) of young refugees and a “multicultural” Berlin, “Baden gehn” by Volker Ludwig and Franziska Steiof (2003), this moral image with music in an outdoor pool without water, is about Berliners and their financial difficulties. The long-time actors Thomas Ahrens and Rüdiger Wandel were moving up to in-house directors. Thomas also became an important author for GRIPS, among other things with “Flo & Co” and “Der Ball ist rund”, a thriller about globalisation. With “Hallo Nazi” (2001), “Kannst du pfeifen, Johanna?” (2002) and “Klamms Krieg” (2003), Frank Panhans caused a sensation as a director in the workshop of the Schiller Theatre, which was our secondary theatre at the time. When the then dramaturge Stefan Fischer-Fels brought me to GRIPS Theater in 2002 - we performed together in the classroom co-production “Lulatsch will aber”, directed by Dietrich Lehmann - I got the assignment from Volker Ludwig to set up a theatre education department at GRIPS Theater. The follow-up work is now being supplemented by workshops. This was followed by further training, play-alongs and the establishment and expansion of children’s and youth clubs. In addition to numerous youth club plays with “Banda Agita” - from “Kontrollverlust” with author Susanne Lipp to “Das Tierreich vom Duo Nolte/Decar” - I like to develop classroom plays as a theatre teacher: First as an actor, with the production of “In die Hände gespuckt” by Christopher Maas, later also as director of ”Fundstücke” by the author Georg Piller, and “Wasserbomben” by Andreas Joppich and Susanne Lipp. With this we established another venue for GRIPS: The school as a stage.

In the years 2007 to 2009, the Berlin financial crisis also had an impact on the steadily poorer GRIPS. With “Wehr dich Mathilda!” – a play about bullying in elementary school – it is again possible to attract masses of school classes, theatre education can hardly save itself from inquiries. A financially strong sponsor had also been found: GASAG, which, together with GRIPS, launched the “berliner Kindertheaterpreis” author competition. Volker Schmidt and Magdalena Grazewicz became the first winners. In November 2008, the large-scale musical production “Rosa” by Franziska Steiof and Volker Ludwig celebrated its premiere. A daring enterprise in tough times, fortunately supported by the Lotto Foundation and the Capital City Cultural Fund, which had already co-financed “Baden gehn” and “Schöne Neue Welt” and without whose help GRIPS could no longer afford a full-length play. At the end of 2008 we flew out of the workshop: the entire Schiller Theatre complex was to be converted into a replacement venue for the State Opera for 23 million Euro. Under the motto “GRIPS makes over” we found our substitute arena in the former “House of Young Talents”, now called Podewil. It is located in the centre of Berlin, near Alexanderplatz – where, as Volker says, the CDU and Springer press wanted us to go 30 years ago! We are moving to the eastern part of the city with five productions. It opened at the end of February 2009 with Philippe Besson’s staging of “Lilly unter den Linden”, a GDR story, appropriate to the change of location and 20 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In 2011, the news that Volker Ludwig wanted to give up the artistic direction after 42 years made waves. He says goodbye with Franziska Steiof’s “So lonely” staged with an unforgettable sensation.

Stefan Fischer-Fels, who worked as a dramaturge and theatre pedagogue at GRIPS Theater from 1993 to 2003, returned to GRIPS as artistic director in 2011. To my delight! Stefan persuaded Volker Ludwig to do his Kästner adaptation “Pünktchen trifft Anton”, a long-running hit like the rock concert staged “Die Fabelhaften Millibillies” for people aged 5 and over, like Ludwig’s bullying piece “Schnubbel” for people aged 6 and over - and many others like Lutz Hübner’s comedy “Frau Müller muss weg”, directed by Sönke Wortmann. With “aneinander vorbei” Stefan introduced the “theatre for people from 2 years of age” at GRIPS Theater. Other highlights: Zaufke/Lunds “Die letzte Kommune” with Dietrich Lehmann as the aged Communard as well as Milena Baisch’s first work “Die Prinzessin und der Pjär” (both 2013) and the discovery of the young director Mina Salehpour. Stefan’s thematic and aesthetic experiments were always worth seeing, thanks to the actors, however, they were increasingly controversial. At the end of the 2015/16 season which was surprisingly soon, he left GRIPS Theater to move to Düsseldorf as the theatre manager. Just as quickly and surprisingly for everyone involved, Volker Ludwig found a new artistic director in me. Although at first I did not take his offer seriously. I was trying to persuade him to take Andrea Gronemeyer when he said: “You could do that too”. I was surprised. Who would use a theatre teacher with no experience as an artistic director for such a position? Volker Ludwig did just that. And with this trust backing me up, I set out to prove the opposite to those who initially wrote me off as a “museum administrator” or “home-grown”. There was an urgent need for action, because the time for planning the new season was running out.

Season 16/17: There were six premieres and the new edition of the GRIPS classic "Eine linke Geschichte". The thematic spectrum ranged from homelessness to IS and homophobia to cyberbullying and family conflicts in “Laura war hier”. With Nadja Sieger, Lydia Ziemke, Maria Lilith Umbach, Sabine Trötschel and Theresa Henning, I was bringing women directors to the house and expanding the collaboration with the authors Milena Baisch, Susanne Lipp and Kirsten Fuchs. Women are still underrepresented in these key positions at the theatre and were also underrepresented at GRIPS. Another project is to portray the diverse Berlin society in its own theatre. I tried to implement this by filling actor positions and a young generation of authors and directors such as Theresa Henning or Mehdi Moradpour. I continued to work with long-term companions such as Yüksel Yolcu, Robert Neumann and Frank Panhans. I brought Rüdiger Wandel (director) back to GRIPS and, in Jochen Strauch, gained a new director for children’s and youth theatre. I built a close cooperation with Vassilis Koukalani from the Athens Theatre “Manufactory of Laughter”.

At the beginning of the 2017/2018 season, Volker entrusted me with the entire theatre management. And at my request, Andreas Joppich became the Managing director who represents GRIPS Theater together with me. Volker Ludwig is still at my side as a consultant. As he himself says: “Preferably at the time when you don’t want it.” That is true. And that is why we get along wonderfully. With the 2018/2019 season, GRIPS is in its 50th, the big anniversary season. “50 Years Future” and “On the Child’s Side” are the slogans that are hotly debated here. How can this special GRIPS story be expressed? The birthday keeps the whole theatre in suspense. How should we celebrate? What should be told? An international symposium on the subject of “Children's Rights in Theatre” as well as a festival with our friends from Greece, India and South Korea are coming up. 50 years of GRIPS Theater also means that our theatre archive will be taken over by the Academy of Arts. The GRIPS Theater is no longer just a theatre, but rather has long been a global research object.

GRIPS has survived 50 years and is bursting with vibrant life. There is no doubt about the meaning of its work: It represents the interests of its audience. A theatre that is needed.

-

Chronology

In 1966 the Berlin Reichskabarett founded the “Theater für Kinder im Reichskabarett” on Ludwigkirchplatz.

The history of GRIPS Theater began in 1969 with the world premiere of STOKKERLOK UND MILLIPILLI (by Rainer Hachfeld and Volker Ludwig) on 17 May. Volker Ludwig directed the theatre.

1972 Relocation to the “Forum Theatre” on Kurfürstendamm and the name “GRIPS Theater”

1974 Relocation to Hansaplatz, the former art house cinema Bellevue was converted and moved into a permanent venue for GRIPS Theater.

1995 GRIPS and the “Carrousel” theatre (formerly the Theater der Freundschaft, today THEATER AN DER PARKAUE) together moved into the “Schiller Theatre Workshop” as a joint studio stage, from 1997 the second venue of GRIPS Theater.

2008 Relocation of the second arena to Podewil in Mitte, called GRIPS Podewil.

2011 Stefan Fischer-Fels took over the artistic direction.

2016 Handover of artistic direction to Philipp Harpain.

2017 Handover of whole direction to Philipp Harpain. Philipp Harpain brought Andreas Joppich to GRIPS Theater as executive director.

2019 Transfer of the archive to the Berlin Academy of the Arts.

2019 June: The celebrations for the 50th anniversary culminate in a two-week festival with a gala evening, an international symposium, a big party on Hansaplatz and guest performances from Egypt, Greece, India and South Korea.

History

GRIPS Theater is a child of the student movement and cabaret. That is the secret of its success. The 50s and 60s were the Cold War period. Anti-communism held the West together, we lived in a deeply anti-enlightenment world.